Does Canada Have Enough Venture Capital?

In Canada, access to venture capital (VC) is cited as a persistent barrier to the creation of world-class firms, prompting the development of programs and funds to overcome it. Policy is operating under the assumption that availability of VC funding is as much a problem today as it was years ago. But what is the current state of VC funds in Canada? Is there a gap? If so, why?

To help us answer these questions, we took a closer look at: the availability of VC funding in Canada in international comparison; the sources and availability of funds by VC stage within Canada; the structure of the Canadian VC system; and the sources of VC flowing into Canada’s leading tech companies.

Contrary to popular belief, Canada performs exceptionally well globally, ranking among the top countries in the world for availability of capital in both absolute and relative terms. Internationally, Canada ranks third in absolute VC dollars invested, behind the United States and China and far ahead of more populous countries such as the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and South Korea. Canada also ranks third on a gross domestic product-basis in VC invested per year, lagging only the United States and Israel.

For a long time, it has been thought that investments from international sources have propped up overall VC funds in Canada, particularly at later stages of growth. But the evidence suggests that this may hold true for earliest rounds of investing as well. In fact, there were 22% more Series A investments made by foreign firms than by Canadian VCs in Canada and more than twice as many foreign firms investing in Canada than Canadian firms making investments. This implies sufficiency of capital for Series A rounds and potentially even later rounds.

The data also helped uncover a major issue with Canadian investors who are less likely to put forward competitive and significant sums of money. Among the companies we analyzed, only 18% financed were exclusively supported by VC firms based in Canada, and nearly 30% had no Canadian investors. In addition, businesses with no Canadian investors received 2.7 times as much money as those with Canadian investors only.

When it comes to leading Canadian technology companies, businesses that relied exclusively on US and other foreign funding in their Series A round eventually raised more money than Canadian-financed firms and were positioned better to become Unicorns.

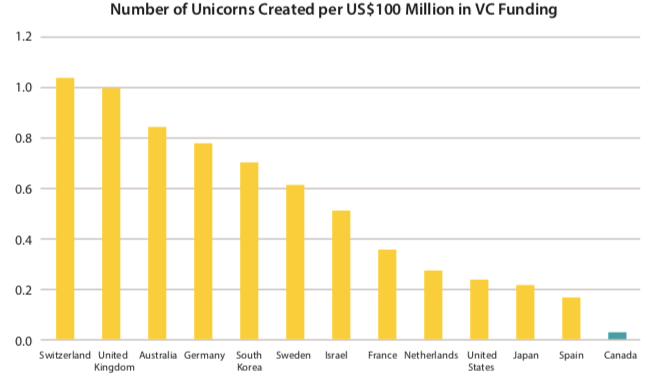

Perhaps one of the main factors shaping our perception of capital in Canada is the lack of results on the scaling front. Canada ranks last among Unicorn-creating Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Although Canada ranks third in the world for the amount of VC invested annually, we place last in the world at turning this investment into Unicorns. The situation is so bad that even if we were to create four times as many Unicorns, we would still be in last place.

The structure of the Canadian VC system also poses some challenges:

- We have too many VC firms with too little capital, potentially causing competition for deals and smaller investments, far less than the companies need to grow fully.

- With smaller investments, these companies have less capital to support losses and important business functions (e.g. marketing and sales) that would help them grow faster.

Our current report has put forward evidence that there is, in fact, sufficient capital for Canadian companies, especially when international flows of monies are considered. Certainly, there is some disconnect between data and the general VC insufficiency narrative commonly heard in Canada. Overall, we believe that significantly more effort should be focused on exploring the underlying causes of the capital (in)sufficiency problem. Only then will we be equipped to design and deliver meaningful solutions that get at the underlying “disease”, rather than the symptoms alone.