by Charles Plant | Mar 13, 2017 | Entrepreneurship

We are pleased to introduce the Narwhal List for 2017. Our previous Impact Brief (A Failure to Scale, February 2017) set out to show that relative to US firms, Canadian companies have historically slower growth rates that make them less appealing to potential investors. We concluded that Canadian businesses have the potential to overcome this issue and position themselves as more attractive investments, but they must be more aggressive, raising capital earlier, more often, and in larger amounts.

Emerging technology companies that wish to attain a significant share of global markets must be able to attract substantial financing. Certainly, this has been the trend for the high-profile group of startups also known as Unicorns. A term coined by the technology markets intelligence firm, CB Insights, a Unicorn is defined as a private company with a valuation at or above $1 billion. All of these firms have been propelled to world-class status by significant injections of early- and late-stage venture capital (VC) funds. In the early stages, Canadian companies must accelerate their growth and their consumption of capital to earn the returns necessary to attract later-stage VC financing, particularly if they wish to reach and compete at the Unicorn scale.

In order to provide a tool to enable entrepreneurs and investors to gauge how attractive firms are from a financial standpoint, we have, in this report, introduced a way to measure Financial Velocity. Financial Velocity is defined here as the amount of funding a firm has raised divided by the number of years it has been in existence. It is expressed in millions of dollars per year. This measure reports the rate at which companies raise and consume capital. We have assembled a list of the top Canadian businesses based on Financial Velocity and are pleased to introduce the Narwhal List. (The term Narwhal was first coined by Brent Holliday of the Vancouver-based Garibaldi Capital Advisors who graciously allowed us to use it.)

The Narwhal List identifies a set of young Canadian companies that have the potential to become companies on the world stage. It also points to possible financial pathways to turn these companies into Unicorns, which are closer to reaching public financial markets. The transition to the Unicorn scale and possibly public listings may give our firms the ability to compete on their own merits and have the currency necessary in public stock to fund acquisitions throughout the world that will lead to greater scale and world-class status.

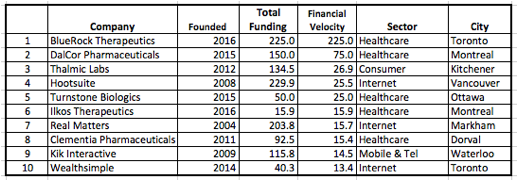

A full up-to-date list of Narwhals is published here. The following short list shows the top Canadian companies as at December 31, 2016.

The Narwhal List 2017

by Charles Plant | Feb 9, 2017 | Entrepreneurship

Policy experts and innovation practitioners have criticized Canada’s scaling problem – its inability to grow and scale companies. This has been a baffling issue because Canada’s technology sector has been successful at starting companies and generating innovations with high potential.

But identifying the root causes of Canada’s scaling problem has been a challenging endeavour. Certainly, the shortage of venture capital (VC) is cited frequently as a contributing factor. The reasoning is that since Canada does not have the capital available to fuel late-stage growth, our high-tech companies are sold well before they have a chance to become globally competitive players.

In this study we wanted to approach the problem from a slightly different angle: Is the way in which Canadian companies raise funds also adding to the scaling problem?

To this end, we looked at 49 private US companies that had received $100 million–$295 million in VC funds since inception. We compared them to 49 of Canada’s largest funded tech companies that had attracted $30 million–$250 million in VC funds per firm.

The data reveal three critical issues:

- Canadian companies wait longer before they start raising funds.

- They raise funds less often.

- They raise less money over time.

These fundraising patterns demonstrate remarkable differences between high-tech firms in North America. What US companies raise in four years, Canadian companies take ten years to raise. US companies (in this study) have six times the capital on hand to spend in their first five years of existence on critical functions, such as marketing and sales, which contribute to growth and long-term sustainability. The result is that, starved for funds, Canadian companies grow at a 47% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) while US firms grow significantly faster at a CAGR of 63%.

These funding trends also create companies that don’t look attractive from an investment perspective, lending validity to questions such as “Why would a US VC who is willing to locate offices in Europe, China, or India relocate to Canada to invest in slower-growth companies?” or “Why wouldn’t a Canadian VC sell a company that cannot get sufficient capital to compete globally?”

In fact, a simple calculation shows that while Canadian VCs earn a 27% internal rate of return (IRR) on a single 5´ exit multiple, US based VCs earn a 115% IRR. In computing the return of a fund as a whole, at a 10´ multiple on a 20% success rate of total investments in a VC fund, the IRR of the fund in the US would be 36% relative to 8% for Canada..(An exit multiple is defined as the terminal multiple at which a project is exited once a desired return on investment is obtained.)

These fundraising and investment patterns over time have given Canada the unflattering label “farm team”, a term that clearly suggests we sell our companies to other countries before they reach global status and scale.

But even though innovation centres, accelerators and provincial and federal governments have shifted their focus from starting to growing companies and to programs to support the scaling of startups and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), it may be too late. By the time Canadian companies need late-stage capital, their historically slower growth rates have already made them less appealing to investors used to dealing with quickly growing businesses.

The lesson for business advisors, policy experts, and government agencies involved in scaling Canadian firms is that we must encourage smaller companies to start raising money earlier, more often, and in larger amounts. This way firms can spend more money on critical functions such as marketing and sales (M&S) and research and development (R&D) and position themselves as attractive investment opportunities to fuel further growth.

You can read a full report on this issue here.

by Charles Plant | Jan 9, 2017 | Entrepreneurship

Improving Canada’s lacklustre innovation performance has been a persistent challenge. Experts continue to blame our inability to turn ideas into tangible products and services on a complex set of factors such as low business expenditures on research and development (BERD) and shortage of venture capital (VC) funds. Yet, even with significant investments and a growing portfolio of policy instruments to spur business innovation and growth, the performance of our national innovation system remains weak.

Given this troubling trend, it is time to go back to basics. We must challenge our core assumptions about what innovation means and how it happens. In fact, one way to boost the commercialization of Canadian products and services is already right under our noses, effectively embedded in the definition of innovation.

Most definitions of innovation echo a common theme which suggests that innovation does not stop, as many would believe, at invention or product development. For an invention to create value or be implemented in the real world, you need to get that invention accepted in the marketplace and in use by consumers. And the only way to do that is to market and sell the invention so it becomes an innovation. The formula for success in innovation then is as follows:

Innovation = Invention + Marketing

Our success as an “Innovation Nation” will depend not only on our ability to come up with novel ideas or inventions but also on our ability to market and sell those ideas. So, how does Canada do in terms of spending on marketing and sales (M&S), particularly when compared to our neighbour to the south?

There is a striking difference in the spending behaviour of Canadian and American firms and their treatment of M&S. While mid-sized US software companies spend, on average, 34% of their revenue on M&S, comparable Canadian firms only allocate 20% of their budgets to those expenditures.

Although marketing and sales are clearly important in getting a technology accepted in the market, the discussion on science and innovation in Canada has paid little to no attention to this part of the innovation formula. Canada also does not have a BERD-like indicator that captures business expenditures on M&S in the technology space.

This neglect of M&S may be one root cause of Canada’s lacklustre innovation performance. We are soft selling innovation and not backing our inventions with appropriate budgets on marketing and sales that are critical to the wider adoption of products and services.

In order for us to become more competitive, Canadian companies must pay more attention to how they market and sell their ideas while policy makers must devise more effective supports that reflect the entire innovation formula—including marketing.

You can read a report on this subject here.

by Charles Plant | Oct 26, 2016 | Entrepreneurship

I was surprised that Finance Minister Bill Morneau warned Millennials that they should “get used to so-called job churn – short-term employment and a number of career changes in a person’s life.” Does this mean he’s giving up on the economy?

I was surprised that Finance Minister Bill Morneau warned Millennials that they should “get used to so-called job churn – short-term employment and a number of career changes in a person’s life.” Does this mean he’s giving up on the economy?

I looked around the other day and decided that as a group, my friends who had stuck with one job or one career all of their lives were on the whole, financially better off than the ones who skipped around between jobs and careers. Even the ones in lower paid jobs had done well financially as they could plan and save knowing how much they were earning.

So is Bill Morneau effectively stating that Millennials should get used to the idea that they are not going to be as well off financially as their parents?

Here’s what happens. If you don’t have a secure career, you won’t spend as much on a house or maybe you won’t buy one at all. After all, Bill’s saying that you better play it safe as you might not know when your next gig will start even though we’re going to train you so that you can keep switching careers regularly.

If you don’t buy a house or spend as much on one then you probably won’t need all sorts of furniture and will not be spending much on renovations. As for buying a cottage, to hell with that idea.

So what happens to the economy when all those job-churning millennials stop spending money? Well the economy tanks and who then will pay for all of us boomers to retire?

What’s the solution? Well it isn’t only training plans. Somehow we need to be de-risking this world of churning jobs so that millennials can plan properly for their future. (And in that way contribute better to boomer retirement – did I mention that it’s still all about boomers anyway?)

by Charles Plant | Oct 19, 2016 | Emotional Intelligence

I was surprised to read in the Globe that Guy Laurence had been turfed as Roger’s CEO but I wasn’t surprised about why. Apparently he had a rocky relationship with the Rogers family who still have control of the company Ted Rogers built.

I was surprised to read in the Globe that Guy Laurence had been turfed as Roger’s CEO but I wasn’t surprised about why. Apparently he had a rocky relationship with the Rogers family who still have control of the company Ted Rogers built.

I had heard from people inside Rogers that he was doing some great work, work that changed fundamentally how they did business and served the customer but that work would take a while to pay off.

While he may have been doing good work he apparently had a brash style and was disrespectful in his dealings with certain members of the Rogers family. In the end, it didn’t matter how good a job he was doing, it only mattered how his bosses felt.

People, (and engineers), you really have to take this one to heart. It doesn’t matter how well you think you’re doing your job. If your boss isn’t happy then you’re toast.

It’s this emotional intelligence thing rearing its ugly head again. We can curse Maya Angelou for saying “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel” but we can’t get around it.

It’s a bitter pill to swallow, particularly for left-brained professionals but technical merit alone won’t help you get ahead at work. Having the right answer all the time doesn’t matter. Delivering expected results will only get you so far.

Ultimately, it only matters how your boss feels about your work. Yes, I know you have to deliver baseline results so you don’t get fired for being a complete write-off but beyond that, success doesn’t come from excellence, it comes from happiness, in this case, your boss’s.

Now I must confess that it took me over 30 years to learn this lesson myself and perhaps that’s why I haven’t had many bosses in my career.

So all of you lawyers, accountants, engineers, scientists and programmers out there, if you want a successful career, repeat after me: “My job is to make my boss happy.”