The Narwhal Project

Three years ago, I started doing research at the Impact Centre at the University of Toronto to discover the root causes of Canada’s challenges in creating a world-leading innovation economy. I thought it would be useful at this juncture to summarize our findings. This report highlights some of the issues we have identified. This blog also announces the move of our content to this new site and the launch of what we are calling the Narwhal Project, an exploration through research of what it takes to scale a tech company. I promise to blog more frequently again but meanwhile, you can check out a summary of our findings in our latest report.

For fifty years, the federal and provincial governments have been spending billions to improve our innovation economy, but without performance improvements. The usual discussion is centered on Canadian businesses and their lacklustre performance on research and development (R&D) and intellectual property (IP) protection. In addition, our productivity has lagged relative to the US because of insufficient investments into productivity-enhancing technologies, along with the lack of available capital and talented people to grow technology firms.

But we believe that a critical challenge is our inability to scale companies to a world-class size. Larger companies boast several advantages. They have greater revenue per employee, pay better salaries, undertake more R&D, and take out more patents.

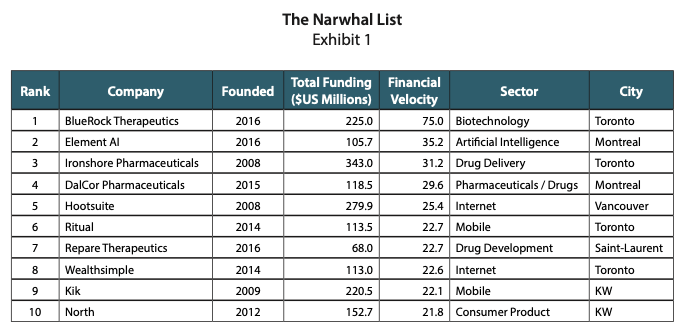

We lack large companies, particularly in the technology sector. We have only one Unicorn (with perhaps another one qualifying but not listed as such at the date of this publication) compared with over 150 in the US. Few tech companies in Canada grow large enough to go public. This means less R&D, fewer patents, and, ultimately, lower income per capita and productivity.

Perhaps the solution to our innovation challenge is not more R&D and more patents, but rather scaling and building of companies. But why are we challenged do this in the tech field? What we have found is that:

- Few Canadian companies are founded in large consumer markets capable of generating the desired scale.

- We invest less per company relative to the US.

- Canadian firms spend less on marketing and sales (M&S), activities that are critical to building the customer base.

- We have fewer qualified people in marketing functions.

The underinvestment and underspending result in lower growth rates for Canadian tech firms compared to their US counterparts. Fundamentally then, Canadian firms do not look as attractive as potential investments due to slower growth. Because of this, they do not attract large amounts of late-stage capital and are often sold before they can scale to world-class size.

All of these factors converge to create serious barriers to growth of Canadian companies, thus necessitating smarter and more strategic thinking about how we will overcome these challenges.

You can get a full copy of the report here.