by Charles Plant | Jul 12, 2017 | Entrepreneurship

It just hit me this morning why the US seems to dominate the world in the creation of innovative companies and products and I think we’ve gotten it all wrong. The Americans aren’t better than the rest of us at research and development and product creation, they’re just better at us in market development.

If you’ve been following my recent research you’ll have seen that I’m on a path to discover why Canada lags many of its peers at the development of an innovation economy. My thesis is that our problem has been misunderstood for years and the problem is not that Canada fails at research and development, patenting or financing startups. The problem is that we’re no good at market development.

I’ve recently started to look at why the US is so good at launching new products and companies. The general consensus seems to be that the US and in particular Silicon Valley is more innovative than the rest of us. But wait a second, this is the country that hasn’t adopted the metric system or replaced low denomination paper currency with coins. This is the country without universal medical care, that still executes citizens, even minors. It is a country with a completely dysfunctional political system and one that is still embroiled in debates over abortion and gay marriage while the rest of the world has moved on. Is this evidence that they lead the world at innovation?

Despite what they claim about innovation and what we think, I think they’re wrong. There is no evidence that the US is better than the rest of us at research and product development. But if they seem to be so good at creating products and companies, what are they better at? I think they’re better at market development.

Over the years across the US, entrepreneurs and companies have perfected the art of market research and in particular design thinking. They have perfected product marketing, developing alliances through business development. They have perfected marketing communications and even more so, sales. They have perfected the art of incubation through such entities as Y Combinator. They have perfected the use of private venture capital and how to best assist the companies reach markets through the assistance these VC firms provide. They have created a machine that can turn average research into world-leading products and companies.

If we want to improve our ability to help innovative new products reach markets we have to stop focusing on the research and development side and focus, as the US has on market development.

SaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSave

by Charles Plant | Jun 13, 2017 | Entrepreneurship

The goal of our current study on Canada’s CMO Search was to examine and compare the quality of marketing leadership in Canadian and American tech companies. We looked at the qualifications of the most senior marketing officer at Canada’s top private venture capital-backed technology firms. Out of the 67 companies we examined, 47 had an identifiable marketing leader. We then compared this person’s qualifications with those of the top marketing officers of 47 U.S. “Unicorns”, which are defined as private companies with valuations of $1 billion or more.

On the whole, we found that Canadian-based marketing leaders are less qualified and less experienced than their American counterparts:

- Thirty-eight per cent of the leading Canadian firms had made the strategic decision to place their marketing functions in the U.S. The U.S-based senior marketing leadership had a job title that featured the term “marketing” in 61 per cent of cases. In Canada, there was a senior marketing person only 35 per cent of the time. In the other 65 per cent of cases, the role was more junior or was included in another position.

- In the case of American firms, marketing leaders had a senior marketing title 90 per cent of the time. In only 10 per cent of the cases we examined was the marketing role part of another title. Compared to Canada, US companies are much clearer as to who is responsible for marketing. The role is more senior on average, and it is not combined with other roles in the company.

- In terms of educational background, there is a clear difference between the qualifications of Canadian and American technology marketers. Forty-eight per cent of Canadian marketing leaders on both sides of the border had no business degree. Ten out of these 23 individuals had a STEM degree (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) degree. Only two per cent had both a graduate and undergraduate degree in business. In comparison, 75 per cent of American marketing leaders had a business degree and 26 per cent had both a graduate and undergraduate degree in business or economics. There were five times as many business graduate degrees among U.S. marketing leaders as there are among Canadian marketing leaders.

- We also looked for experience at growing technology firms. We found that 83 per cent of U.S.-based marketers working for Canadian firms had prior experience with high-growth firms, while only 38 per cent of Canadian marketers had prior experience. Similar to the U.S.-based individuals working for Canadian firms, 85 per cent of U.S.-based marketing leaders had prior experience at a VC-backed high-growth firm or industry leader.

- In terms of international experience, our review of the foreign qualifications of Canadian marketing leaders shows that only 10 per cent of those based in Canada have U.S.-based experience, and 66 per cent have no international experience.

Another factor that is seldom mentioned in Canada is the domestic brain drain. This refers to situations where a foreign tech company such as Google hires Canadians in Canada. These foreign firms attract the best candidates through reputation, better wages and more aggressive recruitment. They get the best talent in the country and train them to do tasks that are not immediately applicable to Canadian tech startups. Thus, the marketing talent trained at certain foreign firms cannot leave directly to help a growing Canadian firm.

When Canadian companies are sold early, very few Canadian tech marketers remain in Canada because they do not want to miss the opportunity to gain experience taking a company from a startup to a global player. Since successful Canadian tech firms often move their marketing offices outside of Canada, there are very few people in Canada developing a base of experience that can help us address our marketing challenges.

With foreign firms taking our best talent, and Canadian firms conducting marketing out of U.S. offices and being sold before they flourish, we have a severe problem. We are not developing a local talent base that will enable us to solve the marketing challenges our firms face. This has implications for public policy and the development of support programs aimed at accelerating the growth of Canadian companies.

Read more about Canada’s CMO Search

by Charles Plant | Apr 13, 2017 | Entrepreneurship

Are we really producing Canadian Tech Tortoises? Recent research we did revealed three critical issues that may be impacting the ability of Canadian businesses to grow rapidly:

- Canadian companies wait longer before they start raising funds.

- They raise funds less often.

- They raise less money over time.

But why do Canadian businesses delay the fundraising process, which is essential to ensuring further growth? Anecdotal evidence suggests two things:

- That many Canadian technology companies wait until their products are completed before raising and spending funds on crucial functions, including marketing and sales (M&S).

- That Canadian venture capitalists (VCs) look for evidence of market traction before considering funding.

This is disconcerting because early expenditures on M&S may lead to faster market traction, more solid growth, and earlier VC funding. But practitioners in the Canadian technology scene have observed that many businesses underestimate the importance of M&S in their formative years.

The goal of this study was to determine whether Canadian technology startups do in fact delay funding M&S activities. To this end, we looked at job classifications of employees at over 900 private Canadian technology companies that had received external investments. We could argue that if Canadian firms postponed spending on M&S, we would expect to see no or few employees in M&S roles relative to total employment in the earliest stages of development, followed by a steadily increasing percentage of M&S-related employees as companies grow.

Job classifications were used as proxy to gain insight into how firms allocate money for various functions within the business. We discovered a striking pattern: while Canadian firms with the lowest recorded levels of external funding (our proxy for growth) have only 13% of their employees engaged in M&S activities, this percentage was significantly higher for businesses that had managed to raise funds. Firms with US$50,000–US$2 million of funding have 24% of their employees engaged in M&S. Thus in the early stages of development, Canadian tech firms are likely to have a larger fraction of their workforce dedicated to research and development (R&D) than to M&S.

A smaller contingent of M&S employees means that less time will be spent on vital startup activities such as market intelligence, product marketing, and business development. Companies that neglect M&S tend to approach the market only when a product is ready, therefore delaying their first revenue and growth.

But how do top technology companies in other countries approach the same issue?

Our analysis of more than 60 tech businesses in the US showed a different recipe for success: firms that scale quickly to US$10 million in revenue spend, on average, 73% more on M&S than on R&D. Leading American firms have 40% of their employees dedicated to M&S.

This is significantly different in Canada where even the highest funded firms only have 31% of their employees in an M&S role. This creates a vicious cycle: fewer M&S employees means less M&S activity, which slows down all the processes needed for customer traction and entry into the market.

Such patterns add to the perception that Canadian companies struggle with commercialization and market adoption. They also led us to conclude that, relative to US businesses, there is a striking difference in philosophy about when to approach customers and markets and that perhaps our technology companies grow more slowly than the leading US companies because they do not spend enough on M&S. Thus creating Canadian Tech Tortoises.

by Charles Plant | Mar 13, 2017 | Entrepreneurship

We are pleased to introduce the Narwhal List for 2017. Our previous Impact Brief (A Failure to Scale, February 2017) set out to show that relative to US firms, Canadian companies have historically slower growth rates that make them less appealing to potential investors. We concluded that Canadian businesses have the potential to overcome this issue and position themselves as more attractive investments, but they must be more aggressive, raising capital earlier, more often, and in larger amounts.

Emerging technology companies that wish to attain a significant share of global markets must be able to attract substantial financing. Certainly, this has been the trend for the high-profile group of startups also known as Unicorns. A term coined by the technology markets intelligence firm, CB Insights, a Unicorn is defined as a private company with a valuation at or above $1 billion. All of these firms have been propelled to world-class status by significant injections of early- and late-stage venture capital (VC) funds. In the early stages, Canadian companies must accelerate their growth and their consumption of capital to earn the returns necessary to attract later-stage VC financing, particularly if they wish to reach and compete at the Unicorn scale.

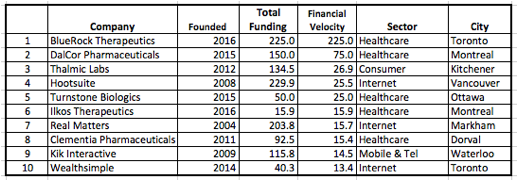

In order to provide a tool to enable entrepreneurs and investors to gauge how attractive firms are from a financial standpoint, we have, in this report, introduced a way to measure Financial Velocity. Financial Velocity is defined here as the amount of funding a firm has raised divided by the number of years it has been in existence. It is expressed in millions of dollars per year. This measure reports the rate at which companies raise and consume capital. We have assembled a list of the top Canadian businesses based on Financial Velocity and are pleased to introduce the Narwhal List. (The term Narwhal was first coined by Brent Holliday of the Vancouver-based Garibaldi Capital Advisors who graciously allowed us to use it.)

The Narwhal List identifies a set of young Canadian companies that have the potential to become companies on the world stage. It also points to possible financial pathways to turn these companies into Unicorns, which are closer to reaching public financial markets. The transition to the Unicorn scale and possibly public listings may give our firms the ability to compete on their own merits and have the currency necessary in public stock to fund acquisitions throughout the world that will lead to greater scale and world-class status.

A full up-to-date list of Narwhals is published here. The following short list shows the top Canadian companies as at December 31, 2016.

The Narwhal List 2017

by Charles Plant | Feb 9, 2017 | Entrepreneurship

Policy experts and innovation practitioners have criticized Canada’s scaling problem – its inability to grow and scale companies. This has been a baffling issue because Canada’s technology sector has been successful at starting companies and generating innovations with high potential.

But identifying the root causes of Canada’s scaling problem has been a challenging endeavour. Certainly, the shortage of venture capital (VC) is cited frequently as a contributing factor. The reasoning is that since Canada does not have the capital available to fuel late-stage growth, our high-tech companies are sold well before they have a chance to become globally competitive players.

In this study we wanted to approach the problem from a slightly different angle: Is the way in which Canadian companies raise funds also adding to the scaling problem?

To this end, we looked at 49 private US companies that had received $100 million–$295 million in VC funds since inception. We compared them to 49 of Canada’s largest funded tech companies that had attracted $30 million–$250 million in VC funds per firm.

The data reveal three critical issues:

- Canadian companies wait longer before they start raising funds.

- They raise funds less often.

- They raise less money over time.

These fundraising patterns demonstrate remarkable differences between high-tech firms in North America. What US companies raise in four years, Canadian companies take ten years to raise. US companies (in this study) have six times the capital on hand to spend in their first five years of existence on critical functions, such as marketing and sales, which contribute to growth and long-term sustainability. The result is that, starved for funds, Canadian companies grow at a 47% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) while US firms grow significantly faster at a CAGR of 63%.

These funding trends also create companies that don’t look attractive from an investment perspective, lending validity to questions such as “Why would a US VC who is willing to locate offices in Europe, China, or India relocate to Canada to invest in slower-growth companies?” or “Why wouldn’t a Canadian VC sell a company that cannot get sufficient capital to compete globally?”

In fact, a simple calculation shows that while Canadian VCs earn a 27% internal rate of return (IRR) on a single 5´ exit multiple, US based VCs earn a 115% IRR. In computing the return of a fund as a whole, at a 10´ multiple on a 20% success rate of total investments in a VC fund, the IRR of the fund in the US would be 36% relative to 8% for Canada..(An exit multiple is defined as the terminal multiple at which a project is exited once a desired return on investment is obtained.)

These fundraising and investment patterns over time have given Canada the unflattering label “farm team”, a term that clearly suggests we sell our companies to other countries before they reach global status and scale.

But even though innovation centres, accelerators and provincial and federal governments have shifted their focus from starting to growing companies and to programs to support the scaling of startups and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), it may be too late. By the time Canadian companies need late-stage capital, their historically slower growth rates have already made them less appealing to investors used to dealing with quickly growing businesses.

The lesson for business advisors, policy experts, and government agencies involved in scaling Canadian firms is that we must encourage smaller companies to start raising money earlier, more often, and in larger amounts. This way firms can spend more money on critical functions such as marketing and sales (M&S) and research and development (R&D) and position themselves as attractive investment opportunities to fuel further growth.

You can read a full report on this issue here.

by Charles Plant | Jan 9, 2017 | Entrepreneurship

Improving Canada’s lacklustre innovation performance has been a persistent challenge. Experts continue to blame our inability to turn ideas into tangible products and services on a complex set of factors such as low business expenditures on research and development (BERD) and shortage of venture capital (VC) funds. Yet, even with significant investments and a growing portfolio of policy instruments to spur business innovation and growth, the performance of our national innovation system remains weak.

Given this troubling trend, it is time to go back to basics. We must challenge our core assumptions about what innovation means and how it happens. In fact, one way to boost the commercialization of Canadian products and services is already right under our noses, effectively embedded in the definition of innovation.

Most definitions of innovation echo a common theme which suggests that innovation does not stop, as many would believe, at invention or product development. For an invention to create value or be implemented in the real world, you need to get that invention accepted in the marketplace and in use by consumers. And the only way to do that is to market and sell the invention so it becomes an innovation. The formula for success in innovation then is as follows:

Innovation = Invention + Marketing

Our success as an “Innovation Nation” will depend not only on our ability to come up with novel ideas or inventions but also on our ability to market and sell those ideas. So, how does Canada do in terms of spending on marketing and sales (M&S), particularly when compared to our neighbour to the south?

There is a striking difference in the spending behaviour of Canadian and American firms and their treatment of M&S. While mid-sized US software companies spend, on average, 34% of their revenue on M&S, comparable Canadian firms only allocate 20% of their budgets to those expenditures.

Although marketing and sales are clearly important in getting a technology accepted in the market, the discussion on science and innovation in Canada has paid little to no attention to this part of the innovation formula. Canada also does not have a BERD-like indicator that captures business expenditures on M&S in the technology space.

This neglect of M&S may be one root cause of Canada’s lacklustre innovation performance. We are soft selling innovation and not backing our inventions with appropriate budgets on marketing and sales that are critical to the wider adoption of products and services.

In order for us to become more competitive, Canadian companies must pay more attention to how they market and sell their ideas while policy makers must devise more effective supports that reflect the entire innovation formula—including marketing.

You can read a report on this subject here.