by Charles Plant | Feb 3, 2014 | Leadership Development

I am reading a book called In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works and Shapes our Lives, which, as you might imagine is the history of Google. As a book, it is a marvellous story about one of the world’s most influential companies.

I am reading a book called In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works and Shapes our Lives, which, as you might imagine is the history of Google. As a book, it is a marvellous story about one of the world’s most influential companies.

The book has a great story about Larry Page and Sergey Brin who hated meetings. Up until 2007, they had a team of personal assistants to do the things that personal assistants do. (Having never had one, I don’t actually know what they do but I hear they can be quite useful if you’re really rich.)

If people wanted meetings with Larry and Sergey, they would ask the personal assistants who would in turn ask them if they wanted a meeting on such and such a topic. However, because they had assistants, it was easier for employees to ask them to meetings where they would have been loath to ask Larry or Sergey directly.

So they got rid of their assistants in 2007 and either took or didn’t take meetings requested through Google Calendar. (It also meant that the other executives assistants had to do more work because Larry and Sergey had no one dedicated to other menial work.)

Without assistants though, The pair became inaccessible because you had to catch them directly to make major decisions. “Larry got rid of his assistants so that he would never meet with anyone who couldn’t figure out how to get a meeting with him.”

If you wanted a meeting, you had to figure out where either one was or where they were likely to be so you could catch them in the hall and harass them.

In a way I can sympathize with them. Employees demand a lot from leaders and can rely on leaders too much. While being accessible is the first step in being a good listener, maybe too much listening is a bad thing. Inaccessibility has certainly worked for Page and Brin.

by Charles Plant | Jan 30, 2014 | Leadership Development

Chris Norton – Cassels Brock

I have picked enough on Holacracy in the last few days but I want to ask one further question. What research did the founders do to arrive at this marvellous new management theory?

- Did they subject it to a rigorous analysis by their peers?

- Did they test out assumptions in small scale before testing it on a whole company?

- Did they compare results between companies or before and after implementation?

OK, that’s more than one question but really, why are so many management theories based on untested ideas? And why are so many people willing to listen to so much untested bumpf and even more, why are they willing to pay so much money to inexperienced consultants who sling this stuff around like they are gods of strategy?

Like many others I have fallen prey to many a new idea and then been disappointed by the results. I don’t mean to rant but you might stop for a second and ask yourself; why are you doing what you do?

- How do you know it’s the best way to get results?

- How will it affect those with whom you work?

- How can it be improved?

- How will you know if you are getting it right?

And when I start spouting off on some new theory, ask me those same questions. I have a friend who shall remain nameless (Chris Norton) who has asked me those questions for close to 40 years. It is an endearing quality of his and I’m thankful often that many years ago he asked me a question like that. His question pops into my mind on a regular basis.

How can you prove that?

by Charles Plant | Jan 29, 2014 | Leadership Development

I’ve been having an interesting exchange with Olivier Compagne, one of the partners at Holacracy One. I wrote a post last week on the subject which was flippant to say the least and Olivier has been good enough to attempt to set me straight on Holacracy. Instead of just lambasting the concept, I thought I would attempt to examine it critically.

I’ve been having an interesting exchange with Olivier Compagne, one of the partners at Holacracy One. I wrote a post last week on the subject which was flippant to say the least and Olivier has been good enough to attempt to set me straight on Holacracy. Instead of just lambasting the concept, I thought I would attempt to examine it critically.

Let’s look first at what Holacracy claims to be:

- There are no titles and no managers.

- Teams are organized around the work, not the people.

- Employees fill many roles in many teams simultaneously.

- Governance meetings structure how the work gets done.

I found this structure quite familiar as from 1979 to 1982 I worked in what is probably quite close to a Holacracy. I was at Thorne Riddell (KPMG) as a Chartered Accountant. We had no titles on business cards and work was organized around audits on which you may be on a number at a time. Your role in each audit depended on the nature and complexity of the audit so you may have had different roles to play at any one time.

This may be a great structure for a project based organization like KPMG but I’m not sure that the same could be said of a non-project based organization such as Zappos. Even though it may work in project based organizations, there were a number of problems with this structure, even at KPMG:

- Working on multiple projects simultaneously meant a fight for resources and at times individuals could be pulled too many ways and end up working ridiculous hours.

- Each project had different expectations and each team had a different culture so what worked with one project may not have not work with another.

- There was no relationship with a “Coach” who could give guidance on career development as we had no one boss.

- Getting feedback on performance in a formal way was project based and didn’t translate to career performance discussions as no one could see the whole picture of your performance.

Strategy execution is one of the biggest problems in business today. In order to implement strategy in an effective manner, each employee must know:

- Exactly what is expected.

- How they are doing.

- How they can improve.

- How they have done.

The problem with Holacracy as I see it is that it just isn’t that easy to execute effectively with such a convoluted non-structure.

- If people work on multiple projects simultaneously without one central boss, it will be very complex to set clear objectives and direction

- Without that one decision maker, the resolution of resource and performance conflicts will be very difficult.

- Individual coaching by someone who knows your work intimately is also very complex.

- Finally, finding out how you’ve done when you’ve worked on multiple teams would be complex and confusing.

Growing revenue and making profits is hard enough as it is, without Holacracy. While I don’t support Bureaucracy, I don’t think Holacracy adds to our ability to execute strategy effectively and for that reason, I’m out.

by Charles Plant | Jan 24, 2014 | Leadership Development

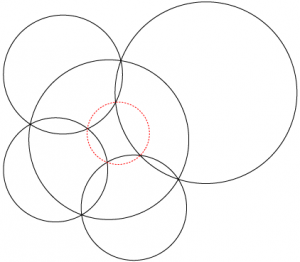

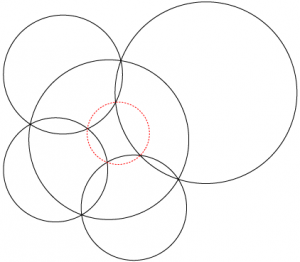

Every now and then you hear of a new management technique that makes you ask – what are they thinking? For me the latest is Holacracy. “Developed by a former software entrepreneur, the idea is to replace the traditional corporate chain of command with a series of overlapping, self-governing “circles.” In theory, this gives employees more of a voice in the way the company is run.”

Every now and then you hear of a new management technique that makes you ask – what are they thinking? For me the latest is Holacracy. “Developed by a former software entrepreneur, the idea is to replace the traditional corporate chain of command with a series of overlapping, self-governing “circles.” In theory, this gives employees more of a voice in the way the company is run.”

As if matrix management isn’t enough, instead of nice tight little grids, we replace lines with circles. I sometimes think people are looking at geometric shapes and wondering how they can build a management philosophy around them. And the worst part is that Zappos has decided that this is the way they’re going to run their company.

When you read descriptions about Holacracy it sort of makes sense which is why I guess that companies would give it a try. Work is organized around what needs to be done instead of around people. People work in multiple circles for different functions. Decision making is integrative. (This must be a new douchebag term I have missed – integrative decision making.)

The big thing about Holacracy is no management. Huh, what’s that? No management? Sounds perfect. Where can I sign up?

OMG, I’m trying to remain open minded but business is hard enough with bad managers. Getting rid of them altogether would be a real trip.

The only great thing Holacracy it is that it will earn a lot of money for the consultants who will help implement it and for the other ones that will help a company recover from it.

Since the idea of running businesses with overlapping circles instead of lines is taken, I think I’ll spend the weekend developing a management theory that uses triangles as a way for organizing work.

by Charles Plant | Jan 22, 2014 | Leadership Development

OK, just one more day on this subject. Pinkie swear. I can’t resist the topic because I’m trying so hard to develop leadership development and management development programs that actually work, not ones that fail. And I must admit that I haven’t cracked the code for success yet either.

OK, just one more day on this subject. Pinkie swear. I can’t resist the topic because I’m trying so hard to develop leadership development and management development programs that actually work, not ones that fail. And I must admit that I haven’t cracked the code for success yet either.

So if you’ve been paying attention to the last two days, I’ve been commenting on the McKinsey article on Why Leadership Development Programs Fail.

The biggest problem I’ve found and that is not mentioned in the article, is that most leadership development programs don’t have a concrete measurable objective. While the article mentions measurement as an issue (and this is a dirty secret of the training industry) it doesn’t go far enough.

If you don’t have a measurable objective, how will you know whether or not you’ve succeeded?

So setting out to implement a leadership development program is a waste of time and money if you can’t describe your objective.

Improve leadership? What kind of namby-pamby motherhood objective is that? We can’t even define what leadership is, let alone agree on how to improve it. And if we can’t even define it, and everyone does it differently, how can we measure it?

What we can do is define management skills (as opposed to leadership skills) as these are functional logical skills that can be measured. These we can set concrete objectives for improving that measure quality, cost, and speed.

So then how do we make sure people are learning leadership behaviours. Well, we expose them to good leaders, good mentors, good coaches. We let them try things out and we let them talk with their peers. This isn’t a classroom program and this is the fundamental problem with leadership development programs, we’re doing it entirely the wrong way.

I am reading a book called In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works and Shapes our Lives, which, as you might imagine is the history of Google. As a book, it is a marvellous story about one of the world’s most influential companies.

I am reading a book called In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works and Shapes our Lives, which, as you might imagine is the history of Google. As a book, it is a marvellous story about one of the world’s most influential companies.