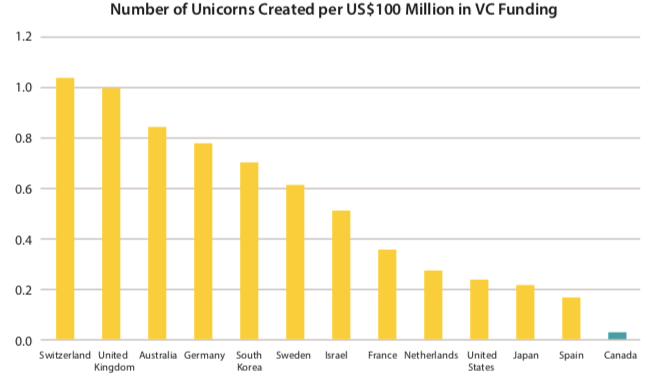

Commonly used productivity and innovation indicators show Canada’s innovation economy declining relative to other countries. Despite large public investments, Canada still trails most of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries on productivity.

The Canadian government has played a significant role in efforts to reverse this decline. For more than five decades, we have seen the proliferation of new programs at the federal and provincial levels aiming to spur productivity and the growth of an innovation economy—yet without significant improvements in country-level data.

This Impact Brief lays out five opportunities for the federal government to change the nature of its programming to reverse the decline. To arrive at our conclusions, we have reviewed over 25 years of federal government budgets and documents prepared by the key innovation department: Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) and its predecessor, Industry Canada.

Opportunity 1. Focus on Commercialization

Budgetary documents show a continued and strong focus on research and development (R&D). Although innovation is emphasized increasingly, commercialization of research remains neglected. This thinking is analogous to the myth of the better mousetrap, that a better product is all that is needed for commercial success. The first opportunity for the government is to revamp their activities to increase their focus on commercialization and related functions, such as marketing and sales.

Opportunity 2. Establish Strategic Objectives

As the key department in the promotion of innovation for the federal government, ISED’s own strategy plays an instrumental role in advancing Canada’s innovation agenda. Although ISED may have an overarching objective guiding its

operations, none of the documentation that we have reviewed pointed to a clear purpose. A significant opportunity is to develop an overarching objective (or set of objectives) for Canada’s central innovation department and turn this into concrete plans whose success can be measured in relation to those objectives.

Opportunity 3. Focus on Demand Creation

Of the challenges that Canada is facing in developing an innovation economy, demand creation is perhaps the most acute. It is likely that we will never have the sufficient local demand to enable our companies to gain experience selling at home before learning how to export. The lack of demand creation programs is a glaring weakness in government programming and one with the greatest potential for positive change and improved results.

Opportunity 4. Improve Program Design Through Rigorous Research and Evaluation

Our innovation-related programs face two key design issues. First, much of the background work done to identify problems in the innovation economy and to inform program design is carried out through opinion-based

research that rarely touches on the underlying reasons for the problems at hand. Second, once programs are

in place, policy-making and program development tend to set unrealistic targets requiring success rates in excess of what is practical. Innovation programs require more rigorous research during design and more realistic targets during implementation.

Opportunity 5. Eliminate Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) Tax Credits

The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) administers the $3-billion SR&ED program, which uses a tax incentive to encourage Canadian businesses of all sizes and in all sectors to conduct R&D in Canada. However, the SR&ED filings and surveys currently conducted by the CRA and other federal agencies (e.g. Statistics Canada) do not allow us to capture net benefits beyond expenditures and simple indicators. In the absence of strong evidence, it is time to seriously evaluate whether Canada actually benefits from the SR&ED program. It is our contention that the time for this program has passed, and that the entire program should be phased out and eventually eliminated.

With such a bold and ambitious move, the federal government could free up to $3 billion a year to focus on demand creation, an area in which Canada has the greatest problem and a large need that is inadequately addressed. It could marry this demand creation to social needs and fund new purchases in areas like health care and clean technology.

In conclusion, if we are to stem the slow erosion of our innovation capabilities, then we must look to opportunities such as those identified above to recast how ISED and other departments (e.g. Finance Canada) provide support to the innovation economy. Without radical changes, we are doomed to continue this slow decline in competitiveness and productivity until

it is too late.